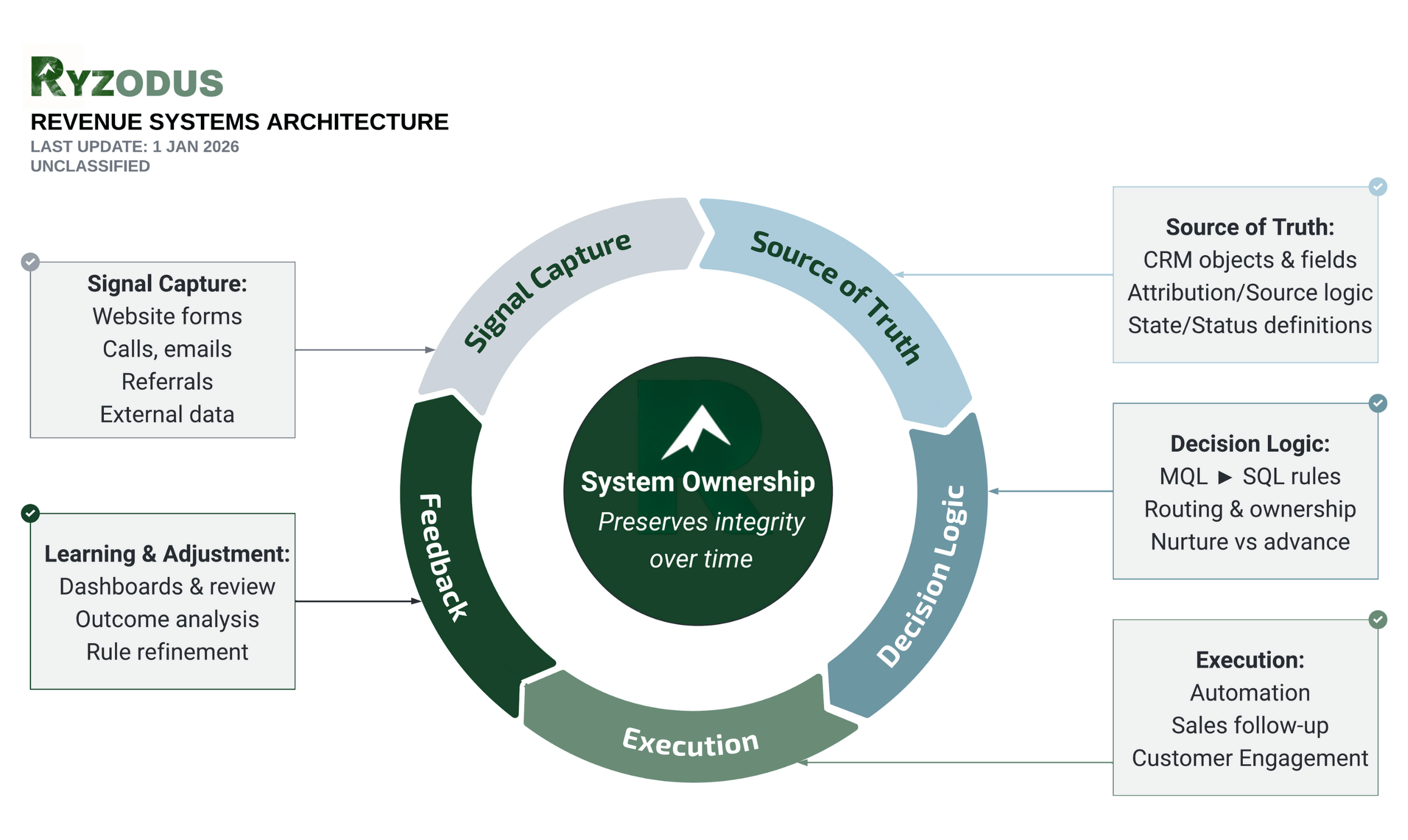

Revenue Systems Architecture

One system. One owner. Modular execution.

These systems exist whether you understand them or not.

Failure is silent at first — catastrophic later.

Marketing hijacked “Revenue Systems Architecture” to mean “how sales and marketing work together.” That’s not wrong — but it’s one layer too abstract for what this really means. That abstraction jump is the problem.

The Problem That Isn’t Named

Most organizations don’t believe they have a revenue systems problem.

Nothing is obviously broken.

Leads are coming in.

Deals are closing.

Dashboards exist.

“We have RevOps!”

And yet…

No one can explain the system end to end.

Attribution is debated instead of trusted.

Small changes feel risky.

Fixes create new problems downstream.

Over time, confidence erodes.

Not because people aren’t competent…

but because the system itself is no longer coherent.

This failure mode is hard to name because it doesn’t announce itself.

It accumulates quietly, disguised as growth, customization, and “temporary” fixes.

This reality layer is often confused with Revenue Operations (RevOps) or go-to-market (GTM) strategy, but it operates at a more fundamental level.

What Revenue Systems Actually Are

Revenue Systems Architecture is the intentional design and ownership of how demand signals are captured, normalized, interpreted, acted on, and learned from across a company’s revenue stack over time.

It governs how information moves from first signal to final decision — and back again — so revenue decisions are grounded in reality instead of assumptions.

That is not marketing.

That is control systems engineering applied to revenue.

The Mechanical Reality of a Revenue System

At its most concrete level, a revenue system is a closed loop.

Signals originate in reality.

They are captured, interpreted, acted on, and then fed back into the system so future decisions can improve.

If any part of this loop is missing — or unowned — the system may still operate, but it cannot reliably learn.

The Closed-Loop Structure

- Signal Capture: Where demand signals enter the system from reality — forms, calls, referrals, external data.

- Source of Truth: Where the system decides what it is allowed to claim — objects, fields, attribution / source logic, state /status definitions.

- Decision Logic: Where the system determines what happens next — routing, MQL → SQL transitions, nurture vs advance.

- Execution: Where actions occur — automation, sales follow-up, customer engagement.

- Feedback: Where outcomes are observed, reviewed, and used to refine future behavior.

- System Ownership: The function that preserves integrity over time by governing the whole, not just the parts.

A Revenue System either Behaves Like a System -- Or It Doesn’t.

If a system:

- Can’t explain where demand came from

- Can’t justify why it took a specific action

- Can’t adapt based on outcomes

Then it does not have Revenue Systems Architecture.

It just has tools.

Think of it like this: If this system is removed tomorrow, what decisions would become guesses?

What This Is Not (At the System Level)

- Tools or Strategy decks

- Funnel diagrams

- Dashboards / Reporting layers

- Collection of high tech automations

These describe artifacts.

They do not describe a system.

Revenue Systems Architecture Defines:

- How demand signals enter the system

- How those signals are transformed into decisions

- How actions propagate downstream

- How outcomes feed back into future behavior

This feedback loop is the system.

Why Revenue Systems Decay

Revenue systems rarely fail all at once.

They decay gradually through reasonable decisions made under pressure, incomplete information, and shifting priorities.

- A field is added to “just handle this one case.”

- An automation is patched instead of re-examined holistically.

- A report is trusted because it’s the only one available.

- A workaround becomes permanent.

Each change makes sense in isolation.

Over time, the system becomes harder to explain, even to the people inside it.

Decay is Structural, Not Personal

Most organizations don’t lose system integrity because of incompetence.

They lose it because:

- No one owns the system end-to-end

- Changes are made locally, without reconciling global effects

- Decisions are optimized for speed, not coherence

- Feedback loops weaken or disappear

As the system grows, these small misalignments compound.

What once felt flexible begins to feel fragile.

Failure Lags Far Behind Cause

One of the most dangerous properties of revenue systems is delay.

- The decision that introduced drift is forgotten

- The symptoms appear months or years later

- The people involved may no longer be there

By the time outcomes degrade, the causes are buried under layers of “normal.”

This makes decay hard to diagnose — and easy to misattribute.

Tools Accelerate Decay When Ownership Is Missing

Modern tools (Salesforce, HubSpot, booking systems, ai/llm, etc) are indeed powerful.

They allow rapid changes, deep customization, and complex automation.

Without clear ownership, this power doesn’t prevent decay — it accelerates it.

The system continues to function.

Revenue continues to flow.

But understanding erodes.

Eventually, no one can say with confidence:

- Who to ask

- What will break if it’s altered again

- Where to make a change

- Why something happened

- Whether a change was correct

At that point, the system still runs, but it is no longer governable.

Decay is the Default

Left unattended, revenue systems drift toward:

- Opacity instead of clarity

- Assumptions instead of evidence

- Local fixes instead of structural integrity

This is not a failure of effort or intent.

It is the natural outcome of complexity without ownership.

Architecture vs Optimization

Optimization and architecture are often treated as the same thing.

They are not.

Both can improve outcomes in the short term.

Only one determines whether improvement compounds — or collapses under its own weight.

Optimization changes behavior.

Architecture determines what behavior is possible.

Optimization

Optimization focuses on improving individual parts of the system.

It asks questions like:

- How do we increase conversion here?

- How do we automate this step?

- How do we speed this up?

Optimization works locally.

When the underlying structure is sound, optimization can be powerful. When it isn’t, optimization amplifies existing flaws.

Over time, this leads to:

- Conflicting metrics

- Fragile automations

- Improvements that don’t persist

- Fixes that introduce new problems elsewhere

Architecture

Architecture focuses on the structure of the system itself.

It asks different questions:

- How does information flow end to end?

- What decisions does the system enable or prevent?

- Where does ownership reside?

- How does the system learn from outcomes?

Architecture works globally.

When architecture is coherent, optimization becomes safer, faster, and cumulative.

When it isn’t, no amount of optimization can stabilize the system.

Ownership is the Missing Function

Most organizations already have people working on revenue systems.

They have marketing teams.

They have specialists.

They have platforms, processes, and regular activity.

An automation someone convinced you is an “AI”.

And of course, our account reps at a dozen different companies.

What they often don’t have is ownership of the system as a system.

"Leadership is not what you preach. Leadership is what you tolerate."

- Jocko Willink

Ownership is a Role, Not a Title

Ownership does not mean authority, seniority, or control.

It means:

- Someone understands how the system behaves end to end

- Someone can explain why it behaves that way

- Someone is accountable for downstream consequences

- Someone stays long enough to see whether changes helped or harmed

- Knows when to plug into an existing automation or make a new one

This role exists regardless of whether it is named.

In many organizations, it simply isn’t filled.

Teams Use Systems. Someone Must Own the System.

Marketing teams are often highly capable.

They create content.

They run campaigns.

They manage channels.

They operate the tools they’ve been given.

But using a system is not the same as owning it and knowing it.

Ownership requires a different mode of thinking:

- Understanding how signals move across tools

- Knowing what can be automated (and what should not be)

- Recognizing when local improvements create global risk

- Designing feedback loops that allow the system to learn

Without that perspective, even strong teams are forced to operate tactically.

Capability Does Not Equal Coherence

As organizations mature, complexity increases.

More tools are added.

More automations are layered in.

More data becomes available.

Paradoxically, this often reduces clarity.

No one is doing anything wrong.

No one is negligent.

But responsibility for coherence is fragmented across roles that were never designed to carry it.

When ownership is diffuse, the system adapts — but not intelligently.

When Ownership Is Missing, Assumptions Fill the Gap

In the absence of a system owner:

- Reports are trusted because they exist

- Automations are left in place because they “seem to work”

- Edge cases accumulate without reconciliation

- Decisions are made based on incomplete understanding

The system continues to function.

But it no longer explains itself.

Ownership Is What Makes Architecture Durable

Architecture defines what is possible.

Ownership determines whether it remains true over time.

Without ownership:

- Architecture degrades into configuration

- Optimization becomes guesswork

- Learning stalls

With ownership:

- Systems remain explainable

- Changes become safer

- Improvement compounds

Ownership is not about hierarchy.

It is about responsibility for coherence.

Ownership Is Often Assumed — Rarely Examined

In many organizations, ownership is implied by role or title.

But system ownership is not about authority over people.

It is about responsibility for structure.

Knowing who approves campaigns is not the same as knowing:

- How signals move between systems

- Where automation makes decisions autonomously

- Which flows exist only because they were never revisited

- What would break if a component were removed/changed

When that understanding doesn’t exist in one place, ownership exists in name only.

The Revenue Landscape (Translation Layer)

Revenue Systems Architecture describes what actually exists.

The Revenue Landscape exists to explain what that structure means in terms leaders use to make decisions — risk, exposure, and consequence.

It does not simplify the system.

It does not replace architecture.

It translates it.

Engineering Reality vs Executive Reality:

Engineers reason in structure.

Executives reason in consequence.

The Revenue Landscape is the communication bridge between the two.

| Engineering Reality | Executive Reality | |

|---|---|---|

| Object relationships | ↔ | Structural dependency |

| Attribution logic | ↔ | Visibility / blind spots |

| Sync failures | ↔ | Fault lines |

| Automation chains | ↔ | Cascading failure |

| Orphaned fields | ↔ | Dead zones |

| Over-customization | ↔ | Landslides |

| No system owner | ↔ | Erosion |

The Revenue Landscape allows leaders to reason about system behavior without guessing — even when they don’t operate the tools themselves.

What This Discipline Enables (Not Promises)

Revenue Systems Architecture does not guarantee outcomes.

It changes the conditions under which outcomes are produced.

When architecture is coherent and ownership is clear:

- Decisions are made with greater confidence

- Changes feel safer because consequences are understood

- Attribution becomes explainable instead of debated

- Improvements persist instead of conflicting

- The system learns from outcomes instead of repeating mistakes

None of this creates growth by itself. It creates the conditions under which growth — if pursued — can compound rather than collapse.

Revenue Systems Architecture does not replace strategy, execution, or effort.

It ensures those things operate on stable ground. The landscape.

What Revenue Systems Architecture Is Not

Revenue Systems Architecture is not a shortcut.

It is not designed for teams looking for quick wins, surface-level optimization, or one-off improvements.

Revenue Systems Architecture is not:

- A marketing service

- A growth tactic

- A campaign framework

- A tool implementation

- A one-time engagement

It does not exist to make dashboards look better.

It does not exist to install software and move on.

It does not exist to optimize locally without accountability for system-wide effects.

Revenue Systems Architecture requires:

- Willingness to examine existing assumptions

- Acceptance of system-level tradeoffs

- Patience to stabilize before accelerating

- Ownership over time, not just delivery

For organizations that want execution without responsibility – this is not the right discipline.

How Work Actually Begins

Revenue systems cannot be responsibly changed until they are understood.

Before anything is optimized, automated, built, or rebuilt, the existing system must be seen clearly – as it actually behaves, not as it is assumed to behave.

That understanding cannot be inferred from dashboards or documentation alone.

It must be constructed deliberately.

The Revenue Systems Audit

The Revenue Systems Audit is the onboarding step for all serious work.

Its purpose is simple:

To load the existing revenue system into one mind well enough that it can be safely owned.

Someone must take responsibility and accountability of the entire system.

During this process, the system is examined end to end — how demand enters, how decisions are made, how automation behaves, and how outcomes are interpreted.

This is not a checklist or a report.

It is the act of building systems-level understanding.

Why This Comes First

Without this step:

- Changes are made without knowing what they affect

- Optimizations conflict instead of compounding

- Problems reappear in different forms

- Responsibility remains fragmented

- It’s just good enough

With it:

- The system becomes explainable

- Tradeoffs become visible

- Decisions feel safer

- Ownership becomes possible

This is why the audit often precedes all architecture, modules, or ongoing work.

Restatement of Reality

Revenue systems exist whether they are named or not.

They shape how demand is interpreted, how decisions are made, and how outcomes are explained quietly, continuously, and often invisibly.

When these systems are understood and owned, they can be governed.

When they are not, they still operate just without intention.

In practice, this usually means a single accountable owner who understands the system end to end and can change it without guessing.

Revenue Systems Architecture does not change that reality.

It simply acknowledges it.